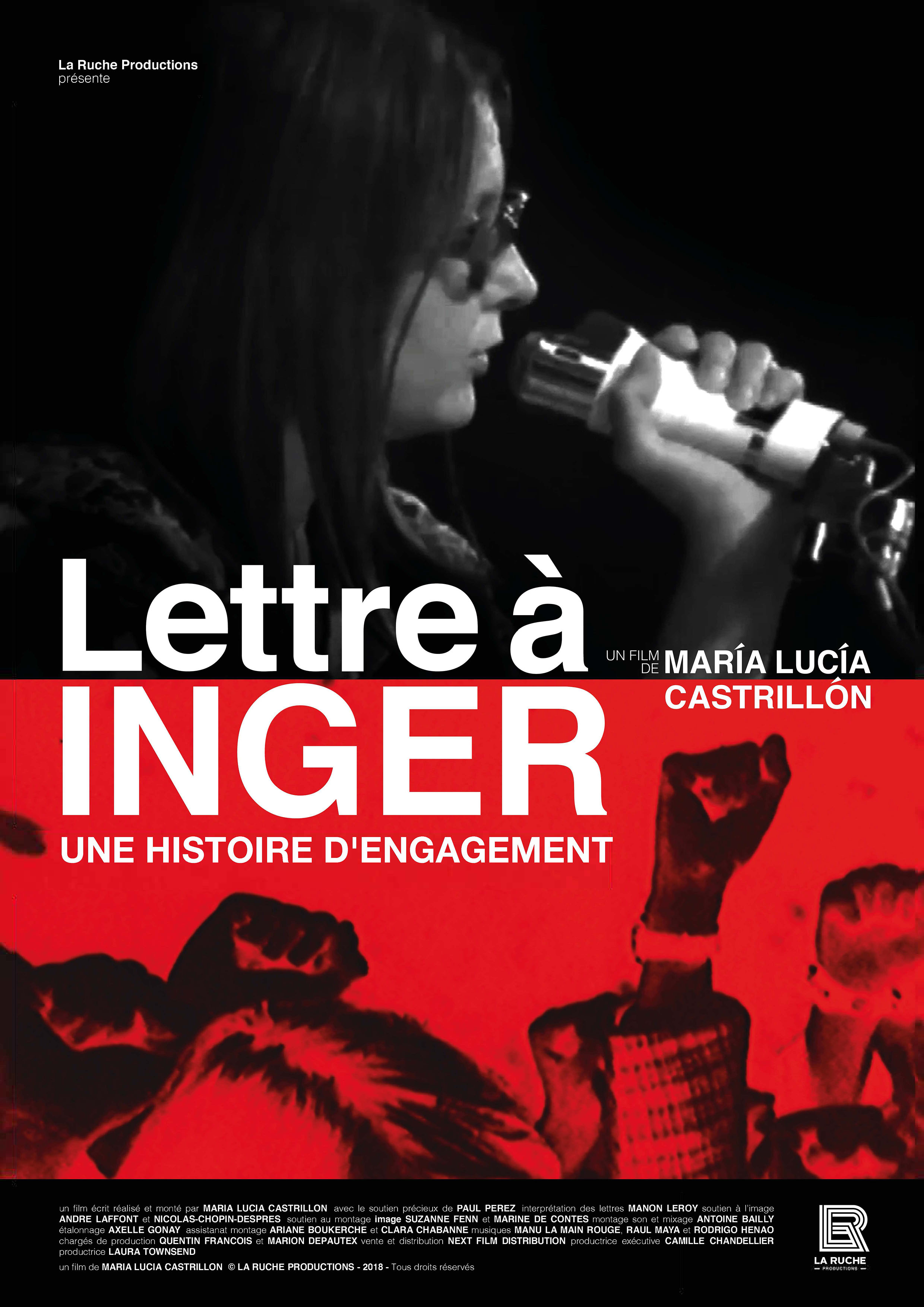

MEETING INGER SERVOLIN

- How did you meet Inger Servolin?

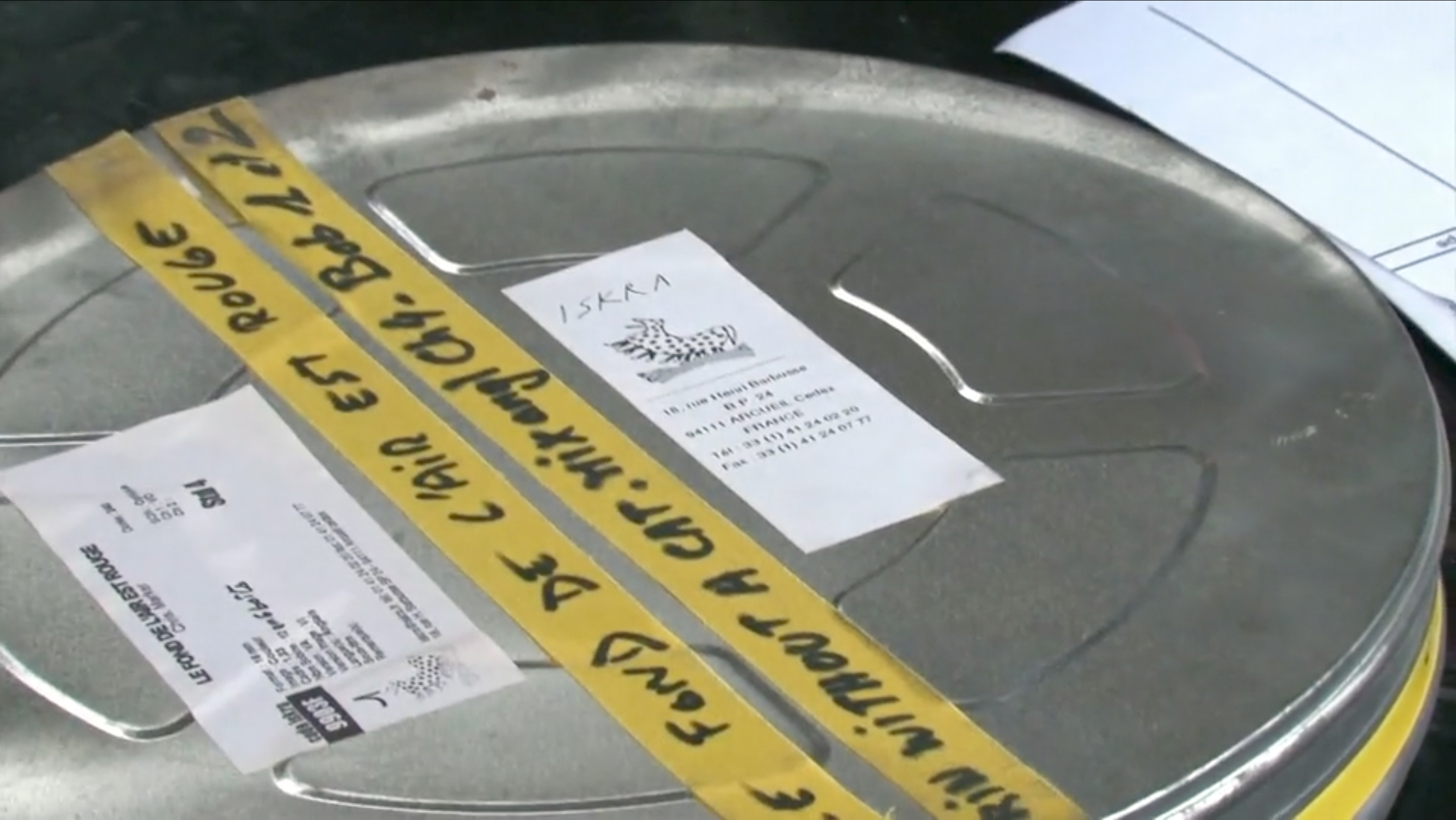

➞ When I finished my film studies in Paris in 1991, I decided to return to Colombia. Before I left, I met a woman called Gisèle Kirjner. She told me about a film she was going to make two weeks later about the women of the Polisario Front in the Sahara. It was being produced by Iskra. I soon found myself on the film crew as an assistant. Inger Servolin was producing the film - Goulili dis-moi, ma sœur : femmes du Sahara occidental -, extracts from which are shown several times in my documentary. The filming was very complicated, but Inger and I had a very powerful experience; there was soul-to-soul communication.

- How did Inger react to the project?

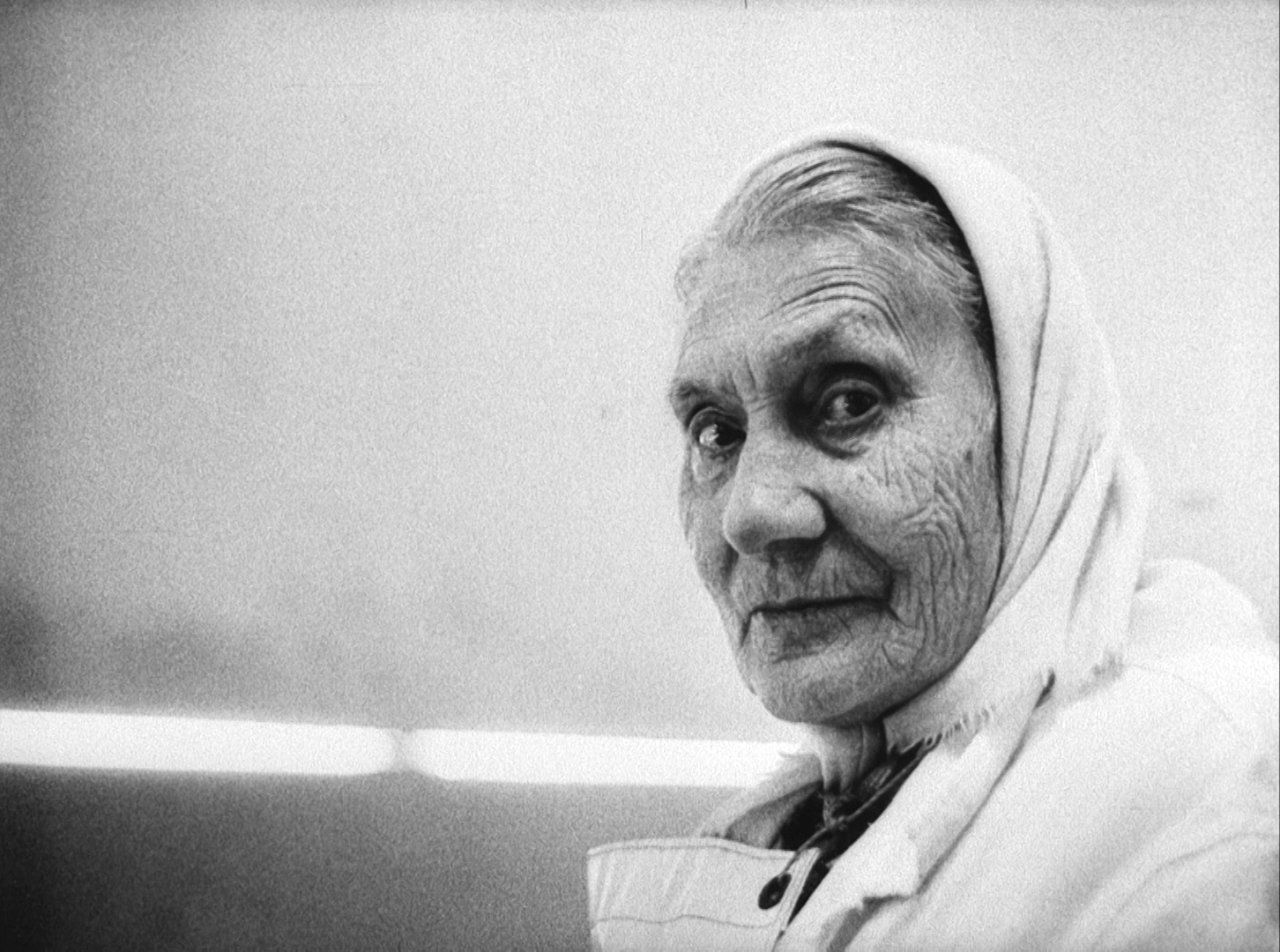

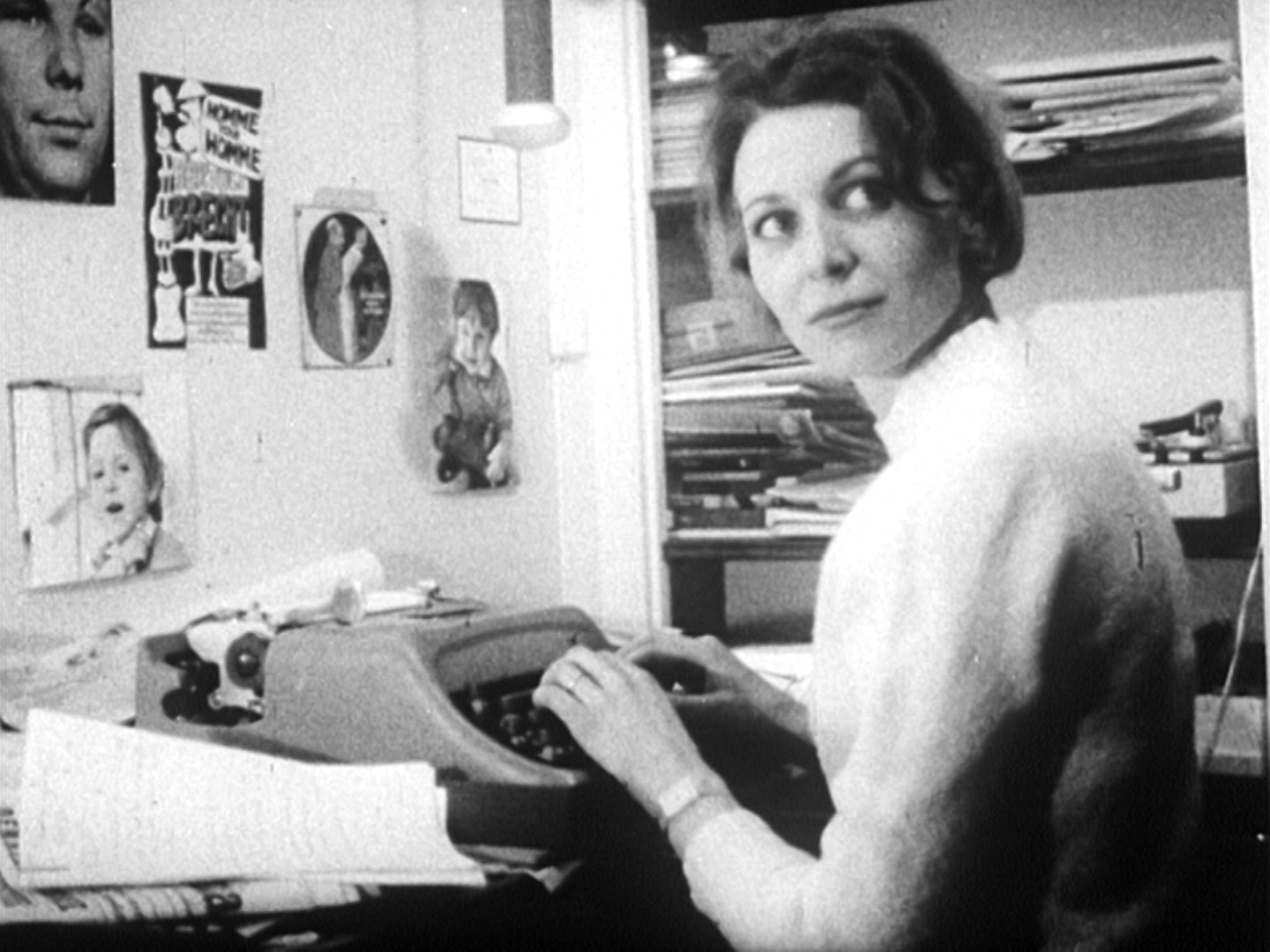

➞ It took me a while to convince her. On the one hand, she understood the value of my project; on the other, she hates photos and showing herself. Her career inspires me, I admire her, I admire the cinema she has produced and her way of relating to the world. I wanted to tell her story, to pay tribute to her, to bring her essential work out of the shadows. The challenge was to tell the story of a woman producer who lived through modern documentary and to show her conception of the profession, her own style of making political films possible in a very coherent way, and who knew how to adapt without selling her soul.

Once Inger agreed to let me film her, she was generous, while of course retaining her legendary discretion. There was trust between us.

- In making this documentary, did you feel close to the spirit of Inger’s early productions, filmed with the means at hand?

➞ Initially, I applied for subsidies. Like any other filmmaker, I applied for funding. Nobody was interested. They were outraged: “A portrait, of a woman no less! Oh no! If only it were Chris Marker again”. Nothing, not even a writing grant from the CNC! I was discouraged and depressed, but I told myself that instead of investing my energy in writing and submitting applications, I had to move forward. My challenge was to be able to bring this project to fruition without betraying Inger, under the conditions I was in. So I made do with what I had.

Where did you start?

➞ I started shooting in 2013 during the Marker exhibition at Beaubourg, a year after his death. I think that, in a way, the circumstances - Marker’s death, the end of an era - helped Inger to accept my film project. The tree that most hides the forest is Chris Marker... Precisely. Inger has worked with many other people, but she got into film because she met Chris Marker. She came to cinema at a time in her life when she wanted to do something that made sense to her. One very important ingredient for her was the political and aesthetic dimension. In 1965, she met Chris Marker. But as she says, if she had met Maspero or anyone else, she could have done something else. I think that Marker and Inger are two souls who understand each other, who have something to say to each other and who are moving forward together.

- Did you discover any other documentary films from the 60s and 70s apart from Iskra?

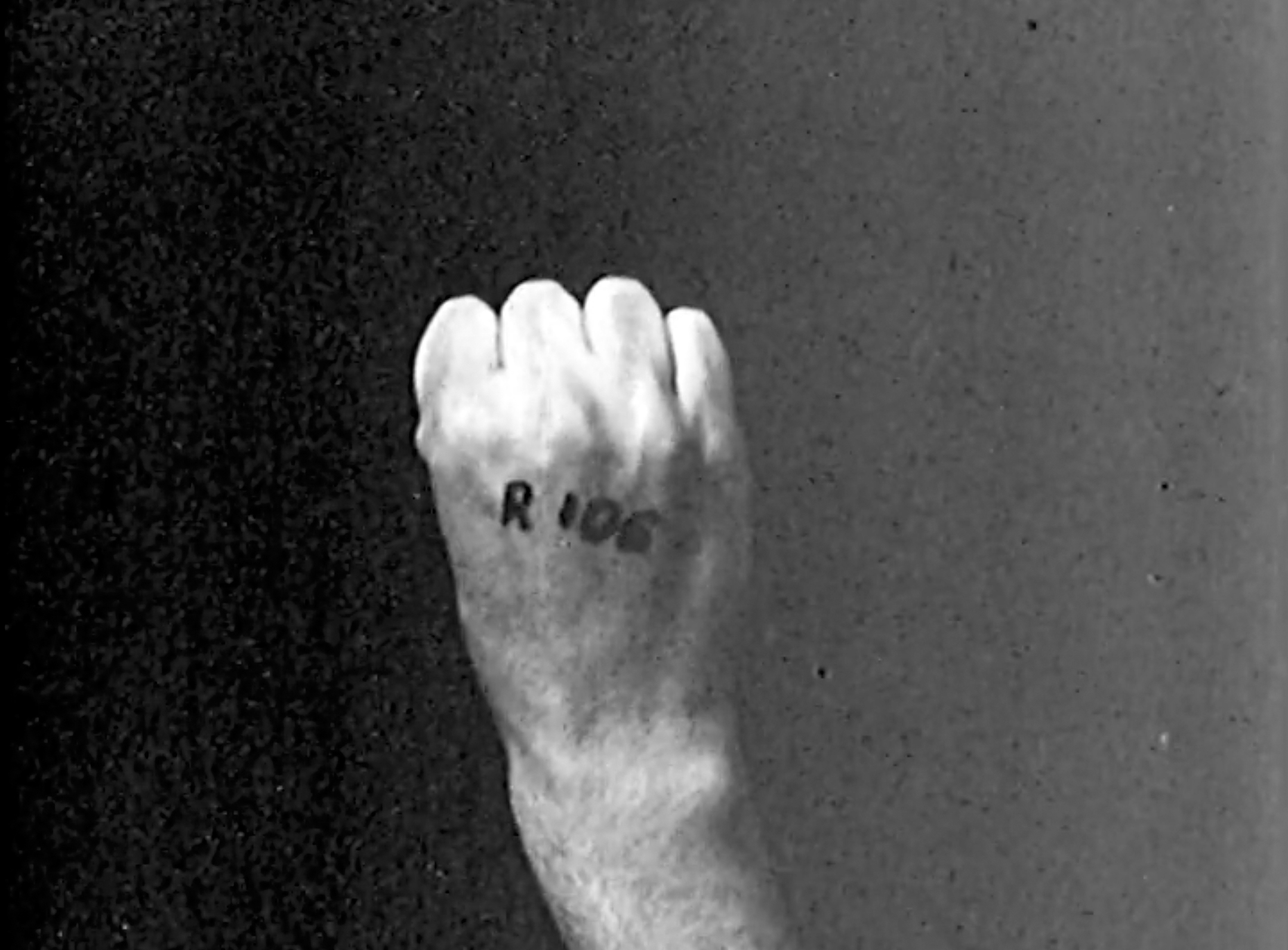

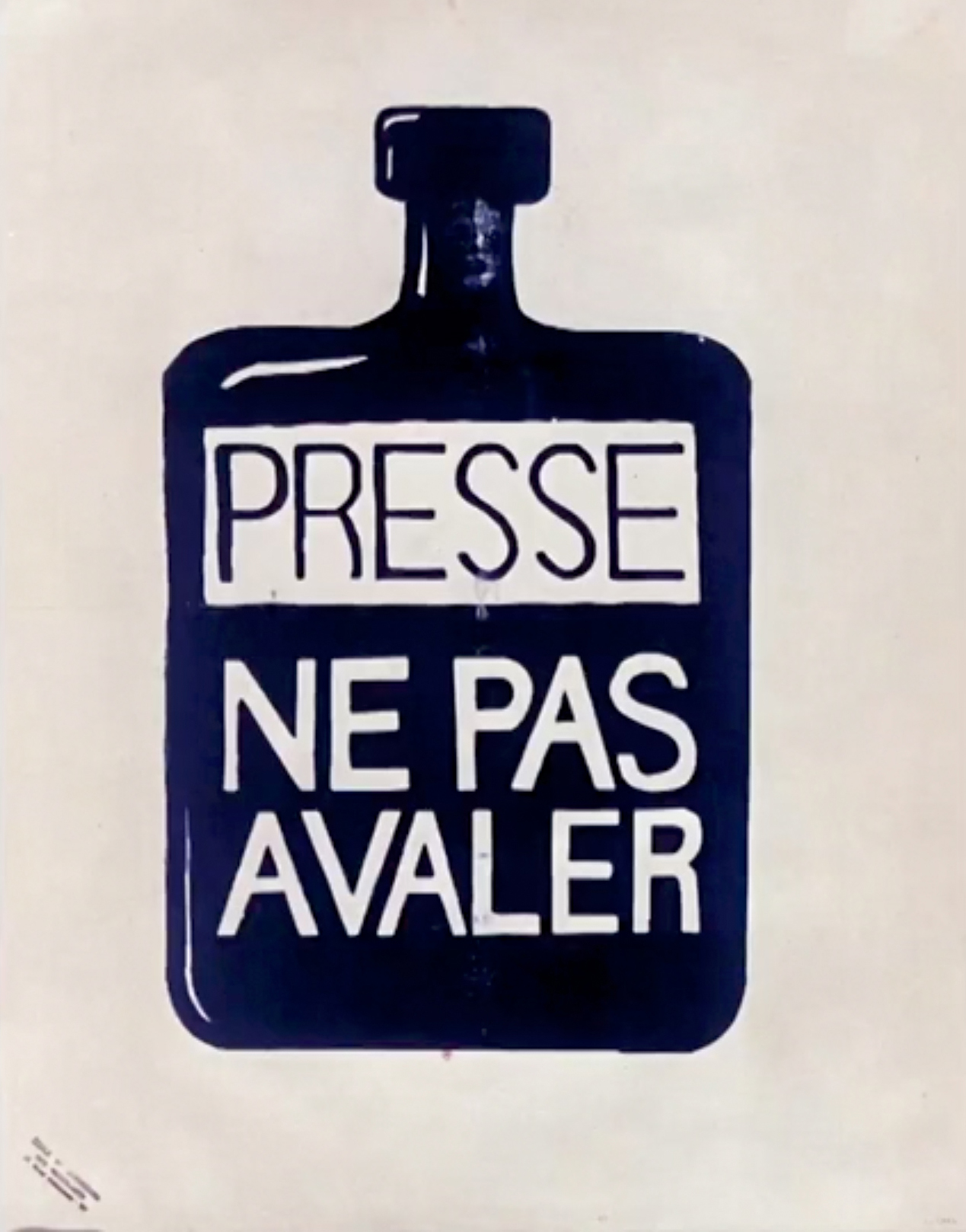

➞ I concentrated on Inger’s beginnings and the origins of her commitment. I watched a lot of militant, working-class cinema, at least from that period, and that’s when I realised the importance of Chris Marker. I’m always touched by the vitality of his discourse and the openness of his analysis. Marker’s political vision in his films is still very present today. Following May 1968, many political film groups were formed. As Pierre Camus recounts in the film, every party and every union had its own. But it lasted three months, a year, four years maximum, like the Dziga Vertov group. The Slon cooperative (Société pour le Lancement d’Oeuvres Nouvelles) founded by Inger, which became Iskra in 73 (Image, Son, Kinescope, Réalisation, Audiovisuelle), is one of the few that still exists.

- Did you work on editing?

➞ Editing was a long, solitary and very trying phase for me. I made I don’t know how many versions, in which my character was diluted either in the history of Slon-Iskra, or in that of the political documentary, or the modes of production... I had to leave out a lot of interesting material, rich testimonies like those of Henri Trafforeti, a member of the Medvedkine groups, Jacques Bidou, a producer who took part in the Communist Party’s cinema group, François Niney, a philosopher and great connoisseur of Marker’s work, and other fellow travellers. I had to turn my back on a lot of possibilities, not without pain, to refocus on my character.

Do you think that Inger’s legacy lives on in the new generation?

➞ Yes, I think there is a younger generation at work, producing things with today’s new tools, but we don’t know them. They’re drowning in a sea of information. And I’m not sure that these young activists know their ancestors and can be considered the heirs of Inger and the militant cinema she produced.

Don’t you want to make your own militant films?

➞ I don’t know if I’d say militant. What I’m interested in is passing on my passion and my love for cinema, and not letting important careers and the things they tell us be forgotten.