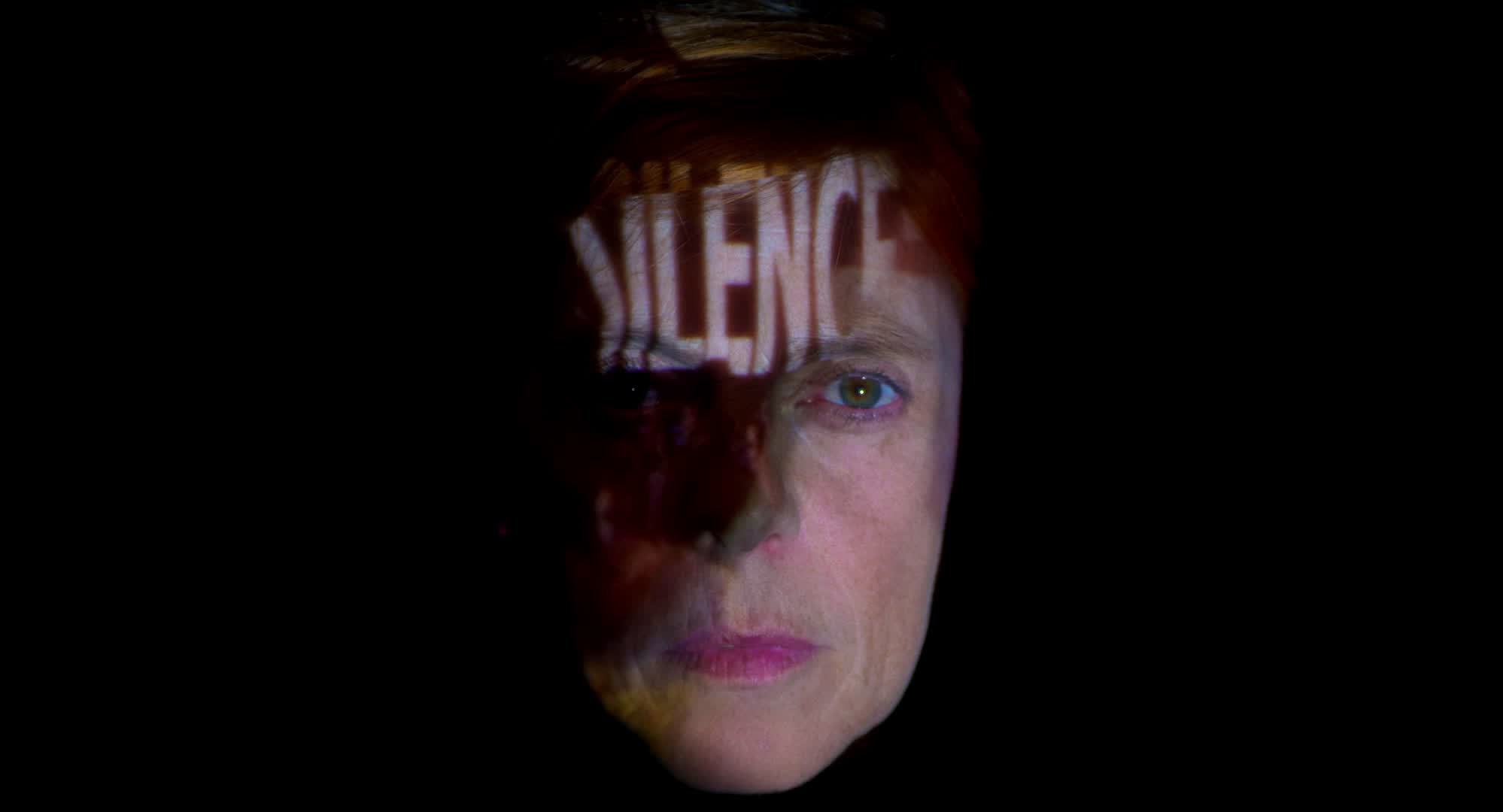

In 1989, at the age of 20, I found out I was HIV-positive. Together with my ‘AIDS sisters & brothers’ -Amel, Alice, Nicolas, and Eder - we tell part of our shared story. A story of rage and the will to live. A cry to finally break the silence.

In 1989, at the age of 20, I found out I was HIV-positive. Together with my ‘AIDS sisters & brothers’ -Amel, Alice, Nicolas, and Eder - we tell part of our shared story. A story of rage and the will to live. A cry to finally break the silence.

I was 20 when I was told I was HIV-positive. I remember it was the fall of ’89. I was young and shocked. AIDS meant death. Death in atrocious conditions. “You won’t see the year 2000!

As HIV-positive people, our lives were subject to political choices, to pharmaceutical laboratories, to therapeutic advances, to who had found the first molecule.Who would market it?And who would benefit from it?We escaped Mr Le Pen’s “Sidatorium”, and the drawing of lots for medicines.We heard the Popes disapprove of condoms and condemn us - sick and therefore guilty.On the other hand, Act up and Aides activists, along with figures from the medical world, worked hard to sound the alarm, to raise awareness of the urgency of the situation, but also to combat fear and exclusion.

In 89, we were all going to die, and many of us left. We had to remain silent, hide ourselves away, unable to share our anguish in the face of this death foretold. And above all, to avoid saying the word “AIDS”, which frightened everyone.

Then hope was born, and with that hope came a reprieve, a suspense in the face of life. Then came the consolidation, the confirmation that we were going to live, perhaps better and better, an almost normal life. At the same time, we saw society ignore us, be afraid of us and finally seem to accept us, a little, so little.

Aids is a silent disease, and even today it’s ingrained in the collective unconscious as a virus of shame, of marginality, of transgression. A disease of guilt associated with death. Taboo. It still frightens, stigmatizes and isolates. Yes, we’re still there. An illness that doesn’t speak out. It took me so many years to decide to tell this story, to feel legitimate.

34 years of medication, 34 years of hospital consultations where I meet regular patients and newly infected people, 34 years of fear and silence too. I should have died, but I lived my life.I’ve loved, then loved again, made plans, made films, become a mother...Always on borrowed time.Surviving.Each of my birthdays is another victory. 34 years of life, a life with this disease, with rage in my belly, with this body I’m trying to tame. A little cohabitation with death.

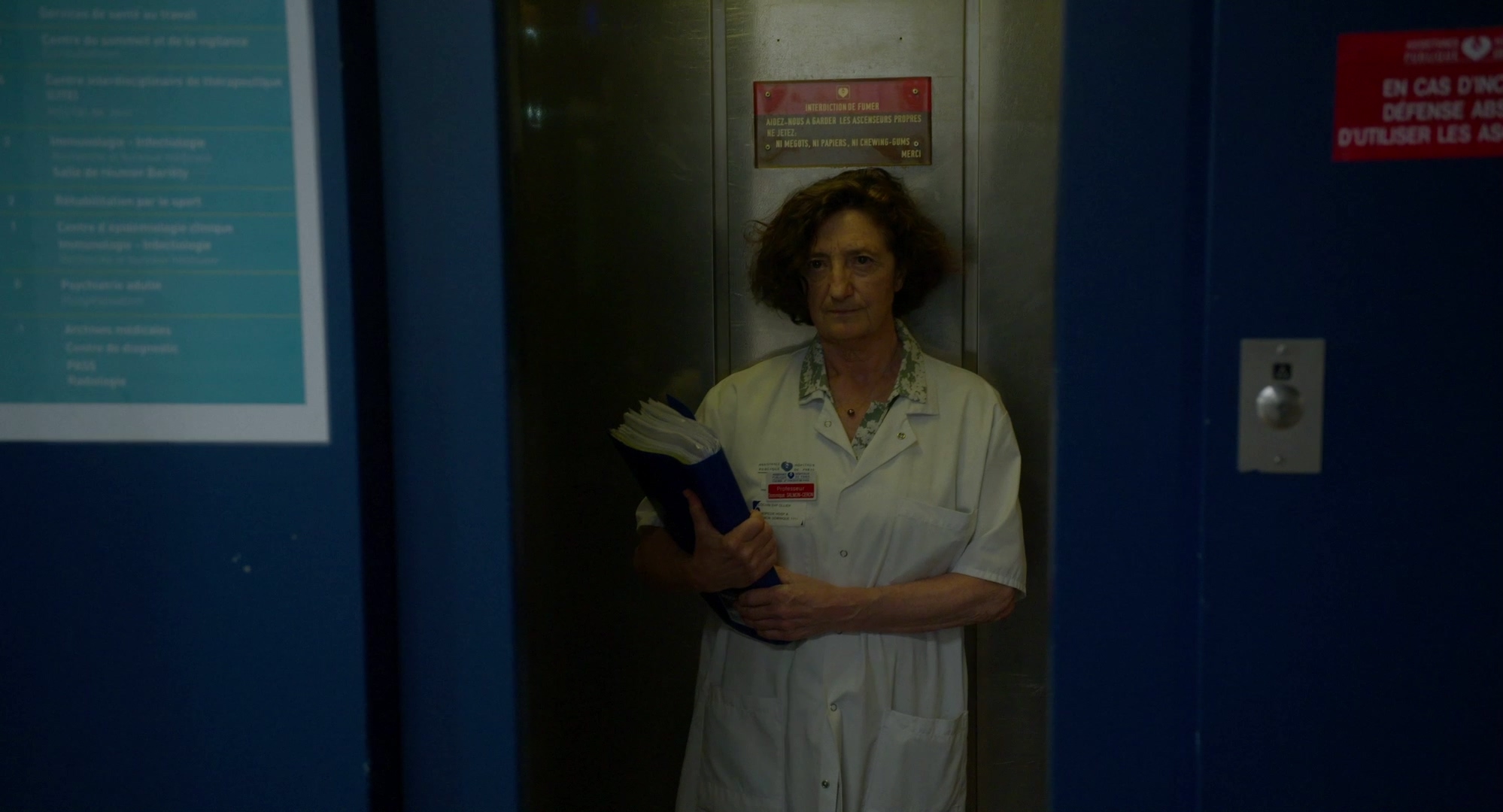

It was during a consultation with my doctor that the idea for the film matured. The consultation is a privileged place, the place where words are set free. With Dominique, my doctor, you can say anything, be reassured, cry. It’s the place where all HIV-positive patients converge, it’s the place where they have to go, it’s the place we all share. The painful place of the announcement. We come here repeatedly. This recurrence is found throughout the film, inexorably, as a reminder of the disease, but also as a place of care and confidence. The hospital plays an important role, with its meandering, tunnel-like corridors, stonework, vaulted ceilings, low-angled light through huge windows, staircases polished by time, lined-up cubicles leading to the consultation room, familiar and impersonal at the same time, distressing and rarely warm.

My personal experience is a collective story. I couldn’t make this journey alone. Today, with Amel, Alice, Nicolas and Eder, we have the strength and the necessary hindsight to look back on this journey with the disease. Behind every HIV, there’s life, life. I speak, they speak... we speak HIV. We are emerging from a heavy and destructive silence. It’s tempting to shut ourselves away: out of fear, denial or shame. I don’t know anyone who shouts “I’ve got HIV” from the rooftops.

What was at stake in the film was for my story and my trajectories to mingle with the stories of other bodies, and for our words, together, to build the narrative. I wanted to mingle with those who, like me, had lived this story in their flesh and gone through all these years without flinching. Those who, deep down, draw on unsuspected resources, with this ability to overcome a traumatic situation, with this desire for immortality. These experiences, both painful and silent, have something to teach us, something disturbing and inspiring to say about our society... and about life, quite simply.

The idea was to get away from the big story and tell, on my own small scale, as a woman, my feelings, my sensations, my memories. And what was important to me was to offer others this space to speak out together, thus becoming a space of liberation, the possibility of putting one’s stone in this everyday struggle, and finally stepping out of the shadows.

That’s what brought us all together. I asked my doctor to allow me to attend consultations so that I could meet other patients. I wanted to find out how, today, on the other side of the disaster, each person deals with their illness, whether or not they accept it, whether or not they live with it in secret, what their struggles are, what has kept them going? How does a life spent living with death teach us about life, and change the way we look at the world? How has illness transformed us?

At the hospital, I met around fifty people. They are heterosexual or homosexual, costume designer, hotel manager, psychoanalyst, accountant, bricklayer, actress, unemployed... Many refused to talk. The fear of exposing oneself, of talking about the disease, challenged me and convinced me even more that a film had to be made.

We talked at length with those who felt the need to talk. Only Amel, Nicolas, Alice and Eder continued this exchange. A relationship of trust was established, with the same deep desire to shed light on a part of this story. A need to tell how, beyond the silence, we are women and men like any others, with this desire to love despite the fear of revealing our illness, to build a future, to have children, to work in this world from which we were in a certain sense rejected. A need to tell the story of our rage and desire to live in a more raw, intense and acute way. Whether it’s the question of mourning motherhood for Amel, love as survival for Eder, living with the virus for Nicolas, the joy of being a mother for Alice, each voice resonates with the questions I ask myself and the sensations I feel. With my brothers and sisters from AIDS, we make this choice together. We are linked by this shared memory, we are survivors.

And then there are those who count in my life, who are part of this story. JP, the man who infected me, is also a survivor. We’ve remained very close, united without ever daring to talk about the disease. Perhaps because we were living it. In this film, I wanted to try to question him, to go back into the past, to better understand how things changed and what JP felt during all those years. And even if the answers remain unanswered - JP isn’t very forthcoming - I think this opened up a breach in the unspoken aspects of our history.

And then, above all, there’s my son. I started writing this film as a letter to my son, whom I was lucky enough to have despite his illness. My son and I don’t talk much about it. He doesn’t ask me questions, but he’s living it in his flesh, and I felt that the film would allow me to pass on to him this collective history, that of the AIDS generation. A story that, for young people, seems to be a bygone era, a story of the past. And yet AIDS is still with us. 6,000 infections a year, and all it takes is one night.

It doesn’t just happen to other people.

She’s 59 but looks much younger. Contaminated by a syringe in the ’80s, she’s a former drug addict. She’s terrified of white coats. A Tunisian with short hair and a matte complexion, she’s beautiful. She’s a costume designer in the film industry, but tells me she works less these days. Ever since her mother died, she’s wanted to talk. She’s always been angry at the disease, but she’s trying to calm down.

Nicolas, tall and sturdy, is 54, my age. Transfused with contaminated blood, he became HIV-positive at the age of 10. He comes from a family of haemophiliacs. The son of a senior civil servant, he distanced himself from his social status to safeguard, as he puts it, “his mental health”. He is deeply involved in the fight against AIDS, on the side of scientific research. He knows all the details of the disease, its consequences, treatments and side effects. He fights to keep up.

A handsome young man of 39, Eder is Brazilian. He comes from a small village north of Rio and ran away from home at the age of 16 to live his homosexuality freely. Infected in 2015, he is part of the generation that did not experience the “dark years”. He arrived in France 10 years ago and now runs a hotel in Les Halles. He’s a romantic, guided, at his peril, by love. Since the age of 20, he has been performing as a transformiste. He changes his skin. He doesn’t think about Aids.

A leading specialist in infectious diseases, she’s a petite woman of 70, with a mischievous eye. She’s the one you can tell everything to : your difficulties, your sorrows, your anxieties. No taboos, no shame. Curious about other people’s lives, she questions, worries and reassures. Her patients need her, just as she needs them to advance her research. She is the doctor for all of us, Amel, Nicolas, Alice, Eder and me. She accompanies us through our lives and our illness. She’s a real companion.